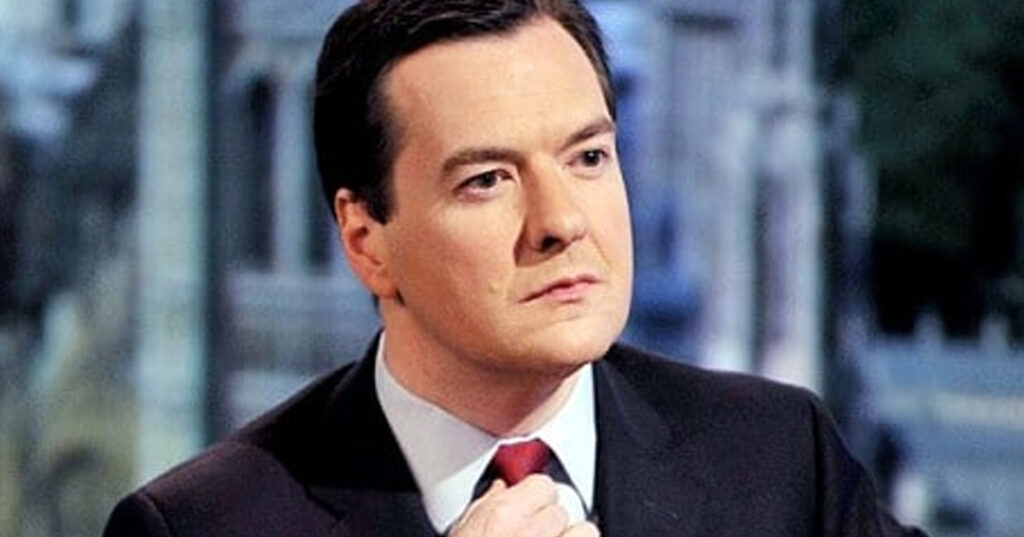

Published in The Sunday Telegraph on 27 November 2011

George Osborne can take comfort from two things as he prepares to deliver a gruesome autumn statement to the voters.

First, they will be more impressed to hear honest gloom than they would be by a cheerful assessment that seems to deny the evidence of their own eyes. Second, nobody believes there is very much he, or any government, could do today to overcome the economic crisis.

Strangely, some voters will feel reassured by a bleak assessment from the Chancellor, because at least it will show that the government realises how bad things are. In our poll three quarters mentioned prices as one of their top three concerns; petrol, energy and food prices were mentioned spontaneously in every focus group. This was followed by fears about finding or keeping a job. But nearly two thirds of those aged 65 or over were concerned about low interest rates for savings – bigger even than the proportion of younger people worried about finding work. Overall, people were evenly divided over whether the situation will improve or deteriorate in the next three or four years. Among the swing voters in our groups there was great uncertainty, but the consensus was that things would get worse before they got better.

International circumstances tell people there is little the government can do about this. Most readily admit they do not understand the Eurozone crisis. But from what they do grasp, the main lesson they draw is that Britain was right not to join the euro. Beyond that, the crisis results from what people see as a southern European tendency to combine profligacy with tax avoidance. Even so, the government seems to many to be right to curb excessive spending as it consequences take such spectacular effect.

The scale of the problem means that measures proposed by either party to promote growth seem piffling. Apprenticeships and work programmes for the jobless are welcomed, but little use if there are no real jobs to go to. Changes to planning laws make people fear for the Green Belt. Temporary cuts in VAT or National Insurance may help for a short time but could exacerbate the debt problem. Building infrastructure sounds appealing but the benefits would take a long time to appear, and anyway, haven’t we run out of money?

When living standards are falling, people are acutely sensitive to the notion that others are getting out more than they are putting in. A widespread feeling remains that many of those living on out-of-work benefits have chosen to do so, and in some cases live more comfortably than others who work at low-paid jobs. On the same theme, there is continued anger about the scale of bonuses paid by bailed-out banks, and their apparently continued reluctance to lend to smaller businesses at reasonable interest rates. The government’s words and deeds in these areas can help to indicate to people whether it is on their side or not.

Ultimately, whom voters trust more on the economy depends on the big questions. Most people say they have been affected by “the cuts”, because anything that erodes their standard of living (stagnant private sector wages, higher prices, trouble getting a loan) is regarded as a “cut”. And as far as public spending is concerned, the cuts are everywhere. Few believe that the overall NHS budget is being protected, and even if it is this is irrelevant if people have seen changes to their own local services which look to them like cuts. (We found that nobody knew the International Development budget was being increased, and more interestingly, almost nobody knew what it was. It sounded to many like a scheme to develop foreign trade links – which they would have considered a rather better investment than aid).

Consequently, many echo the Labour complaint that the cuts are going too far and too fast. But on the question of government spending, they also know that the inevitable corollary of cutting less and more slowly is that Britain will be borrowing more for longer. Intuitively, then, many or even most people do accept, however reluctantly, that the coalition is right on this central question. Very few thought the economy would be in a better position today had Labour won the election – indeed they were more likely to think it would be worse.

The coalition’s argument that we inherited this mess from Labour is wearing thin. In our poll only 40% named the last government as being among the top culprits for the economic situation, behind British banks and only just ahead of “people who borrowed more than they could afford”. Swing voters chastised Labour for failing to see the crisis coming and make provision, as well as for spending more than Britain could afford. But even those who felt this said they were fed up with hearing it from the government.

If the Chancellor’s message this week seems unpalatable, it will at least have the merit of being, for voters, believable. Over-claiming on the economy would not just be unconvincing, it would reinforce persistent perceptions that he and his party are out of touch with life as it is lived by most people.