Published in the Daily Express on 26 March 2024.

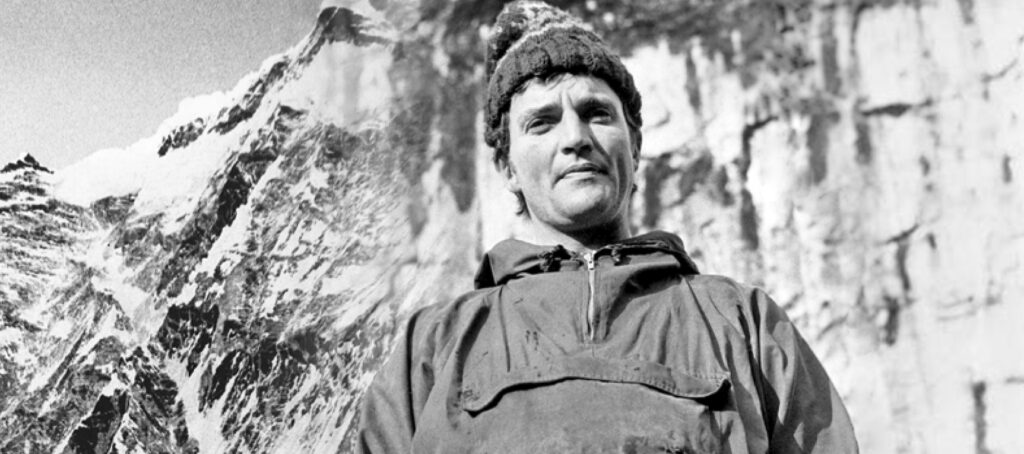

SAS legend Michael ‘Bronco’ Lane, who has died at 78, didn’t let a bit of frostbite while conquering Everest halt his military career… even though it cost him four fingers, a thumb and all ten of his toes.

IN THE SAS, there are legends, absolute legends and then there is… Major “Bronco” Lane. Both as a mountaineer and as a soldier, he reached heights of resilience and bravery that defy belief.

It was General Sir Michael Rose, the former commanding officer of the SAS, who once summed up one of the most remarkable military careers of all time when he said: “Bronco Lane is an exceptional soldier whose spirit of adventure and readiness to take risks has led him to the most extreme and dangerous places on Earth – including the summit of Mount Everest.”

Sadly, “Bronco” died on Friday aged 78, but he leaves behind a legacy and stories of derring-do that will live on for generations. His SAS career spanned more than 18 years, during which he rose from trooper to major, serving for some of that time in the coveted rank of regimental sergeant major.

In an elite fighting force in which heroics are all too common, Lane became much more than a soldier – he was also an adventurer, climber and author.

I feel privileged to be the custodian of Lane’s gallantry and service medals, which form part of a major Special Forces collection I have amassed over the past four decades. I’m also proud to be able to tell his life story because he co-operated with me for his write-up in my book Special Forces Heroes.

Michael Patrick Lane was born in Manchester on July 22, 1945. He enlisted into the Royal Artillery in his home city on September 20, 1961, aged 16, and joined the SAS some six years later.

Even before he became renowned for his courage in the face of the enemy, he had already made a name for himself within the SAS for the circumstances under which he conquered the world’s highest mountain.

Our team had no prima donnas, and unselfishness was displayed to a very high degree.

Lane was a keen mountaineer and, in 1976 at the age of 30, he was part of the Army Mountaineering Association expedition to Mount Everest. Indeed, he was chosen to be one of the “summit pair” – the two sent to the top of the mountain, which stands at 29,035 feet. At this time, climbing Everest was extremely rare and Lane was one of the first Britons to conquer the mountain.

On the way down the pair encountered a “white out”, which led to conditions described by the expedition leader as “the worst under which the mountain had ever been climbed”.

It was only when they tried to thread up a new oxygen bottle during an icy blizzard that Lane realised the extent of his frostbite. As he removed his right glove, the ends of his four fingers and thumb remained in the garment. He eventually lost all 10 toes to frostbite, too.

However, were his mountaineering days and SAS career over – or did he feel sorry for himself? Not a bit of it. He went on to climb Everest twice more, be awarded the Military Medal for bravery in Northern Ireland and even play roles in the Iranian Embassy siege and the Falklands War. The recommendation for his British Empire Medal (BEM), announced in the London Gazette on January 1, 1977, detailed the full extent of Lane’s courage on Everest. The other soldier to reach the summit was his friend John “Brummie” Stokes.

Losing a climbing companion is a stark reminder that you do not conquer mountains but sneak up and down when nature has turned her back.

Their expedition leader wrote: “As they began their descent the weather continued to worsen. They were climbing under ‘white out’ conditions which became exceedingly dangerous. Their progress was slow. When darkness fell they were still some way from Camp 6 and so were forced to bivouac for the night on the exposed and dangerous knife-edge ridge. They passed the night at this extreme altitude and in intense cold sustaining each other as best they could. Chances of survival under these conditions were slim but they were a very close pair who had worked and climbed together for many years. And so were able to rise to this supreme test of endurance.

“They displayed extreme heroism in encouraging and helping each other. When morning came, they were exhausted, frostbitten and barely alive but they forced themselves to continue to climb down. They were met by the rescue party that had moved up to search for them. It was then several days before they were eventually helped down to reach the safety of Base Camp.

“From my personal knowledge of high mountains, based on many expeditions to the highest peaks of the Himalayas, I consider the conditions under which they reached the summit of Everest were the worst under which the mountain has ever been climbed. There are few other mountaineers who could have survived such conditions. It was only their extreme valour, determination and sound training that enabled Lane and Stokes to reach the summit of Everest and return to tell the tale.”

Lane’s sympathy was not for his own injuries but for a colleague who died after falling down a crevasse on the ascent.

He recalled: “Our team had no prima donnas, and unselfishness was displayed to a very high degree. Unfortunately we lost Terry Thompson in a tragic accident, which marred our ascent. Losing a climbing companion is a stark reminder that you do not conquer mountains but sneak up and down when nature has turned her back.”

With typical modesty, Lane made only a short reference to his expedition in his book Military Mountaineering, 1945–2000, published in 2000. He failed to make any mention of his injuries and devoted just one paragraph to his and Brummie’s fight for life during their descent: “By now the weather had worsened and our only option was to make an emergency bivouac in a small hollow. Taking turns to breathe the life-giving oxygen, we sat out the seemingly endless night, shivering violently and rubbing each other’s bodies to stay awake and alive.

A surgeon amputated everything and I was nearly as good as new!

“Occasionally hallucinating, it was a frostbitten, exhausted, dehydrated but extremely grateful pair that witnessed the windless dawn. From the depths of his wind-proof suit pocket, Brummie produced some long forgotten pieces of Kendal Mint Cake for breakfast which, despite being covered in weeks of fluff and assorted debris, proved to be delicious.”

Lane was once asked if the expedition to Everest had ended his career and he shot back the response: “Good God, no. A surgeon amputated everything and I was nearly as good as new!” “But,” continued his questioner, “you didn’t have any toes – and only one hand of fingers?” Lane replied: “Yes, but they made special boots for me in Hereford and extended the safety catch on my Armalite rifle and I was fine. You know, fine.”

It was remarkable that Lane continued to serve with distinction in the SAS, with whom much of his most valuable work was carried

out in Northern Ireland.

He went on countless tours to the Province, during which he was awarded the MM for his work in “Operation Gingal” – an attempt to “neutralise” part of an IRA Active Service Unit (ASU) in early 1979 – less than three years after his near death on Everest.

Lane and another member of the SAS were in an unmarked car when they were alerted that terrorists had gone to a hidden arms dump to retrieve their weapons for a mission. The arms – waterproofed weapons buried in the ground – had been found days earlier by Special Branch and fitted with transmitters. The transmitters had gone off when they were moved and the SAS was sent into action to try to prevent a bombing mission or an assassination.

Lane and his colleague found the car containing four IRA men and there was a shoot-out on the Crewe Road, near Maghera, County Derry, at 9pm on January 24, 1979. Details of the incident are sketchy but the IRA is said to have opened fire first, spraying the undercover soldiers’ car with automatic fire.

Lane was hit in the arm and his colleague took a bullet in the back – but they also succeeded in shooting and wounding one of the terrorists. The IRA car eventually sped off and, once it was a safe distance away, the IRA men abandoned their vehicle and made their getaway, leaving a trail of blood in the snow.

There is little doubt that they were on their way to carry out an attack – four rifles and a parcel bomb were found in their car. Lane and his SAS colleague were taken to hospital but neither was seriously hurt.

Whatever way you look at it this adds up to a very considerable success.

Brigadier Colin Shortis wrote to Lane just four days later to congratulate him on his bravery: “I was delighted to hear of your swift recovery. And send my warmest congratulations to you and your troops on the very successful outcome of Operation Gingal… I am very satisfied by the overall result; not only have you dented the ASU’s confidence very considerably but you have made a very positive contribution to the morale of the more vulnerable civilians, UDR [Ulster Defence Regiment] and reservists in the area.

“As well as that we have four traced weapons with intelligence potential and one man charged, with hopefully more to come. Finally, at least one life and possibly more were saved. Whatever way you look at it this adds up to a very considerable success.”

Lane continued to serve in the Army long after receiving the MM. This award is believed to be unique for Northern Ireland in that it was both “gazetted” – made public – and it named him as a member of the SAS.

Lane played an active role in the operations room during the Iranian Embassy siege of 1980 and was also present with the SAS during the Falklands War of 1982. He was finally discharged from the SAS on February 8, 1987, after 25 years’ service in the Army – most of them in the SAS. After leaving the Forces, he sought to play down his courage and repeatedly declined to write, or talk, about his bravery in the heat of battle because he refused to compromise what he felt was the code of silence of the SAS – or endanger any future operations. In short, many felt his courage was matched only by his principles.

However, as well as his book on Army mountaineering, he wrote an environmental thriller, Project Alpha, in 2004.

He retained a black sense of humour throughout his life. When, some years ago, he was contacted by the National Army Museum about the loan of memorabilia from his 1976 expedition, he offered his ice axe, along with his frostbitten fingers and toes, which, it emerged, he had preserved in formaldehyde and kept in the SAS’s regimental mess. The toes were not in good enough condition to be exhibited but the fingers were placed on display on a wooden plinth and later returned to Hereford for safekeeping. Lane, who had a daughter by his first marriage, leaves a widow, Sue, to whom he was married for 10 years. The couple lived together in Herefordshire. However, in the final years of his life, Lane was in poor health and he spent his last days in a nursing home in the county that he loved so much.

The SAS’s motto is “who dares wins”. If ever a single member of this elite unit epitomised those three words, it was Major Michael “Bronco” Lane MM, BEM.

DOWNLOAD PDF