Published in Britain at War in January 2023.

Boy 1st Class John Travers Cornwell VC

His life was short but the extent of public mourning over his death was nothing short of astonishing, while his fame has lived on for more than a century. Jack Cornwell, the boy sailor who was hailed a hero far and wide for his bravery at the Battle of Jutland, was, at just 16 years old, one of the youngest recipients of the Victoria Cross (VC).

John Travers Cornwell, always known affectionately by family and friends as “Jack”, was born in Leyton, Essex (now part of Greater London) on January 8 1900. The son of working-class parents, he eventually had a sister and three brothers, as well as two half-siblings from his father’s first marriage. His father, Eli, had spent 14 years in the Royal Army Medical Corps and he had also undertaken a variety of other jobs including working as a milkman, male nurse and tram driver.

Jack Cornwell was initially educated at Farmer Road School and later, after his family moved to Manor Park, at Walton Road School, which he left aged fourteen. At school, he was considered quiet, reserved and dependable. After leaving school, Cornwell worked as a delivery boy on a Brooke-Bond tea van but at the same time he harboured a desire to join the Royal Navy. His parents, however, were against the idea and urged him instead to concentrate on his activities as a Boy Scout.

After the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, Cornwell attempted to join the navy but was initially rejected as too young, aged just 14. However, he tried again the next year and was eventually accepted on July 27 1915 at Keyham Naval Barracks, Devonport, Plymouth. His training began four days later, by which point his father, then aged 63, had managed to re-join the Armed Forces, serving as a Private in the Royal Defence Corps.

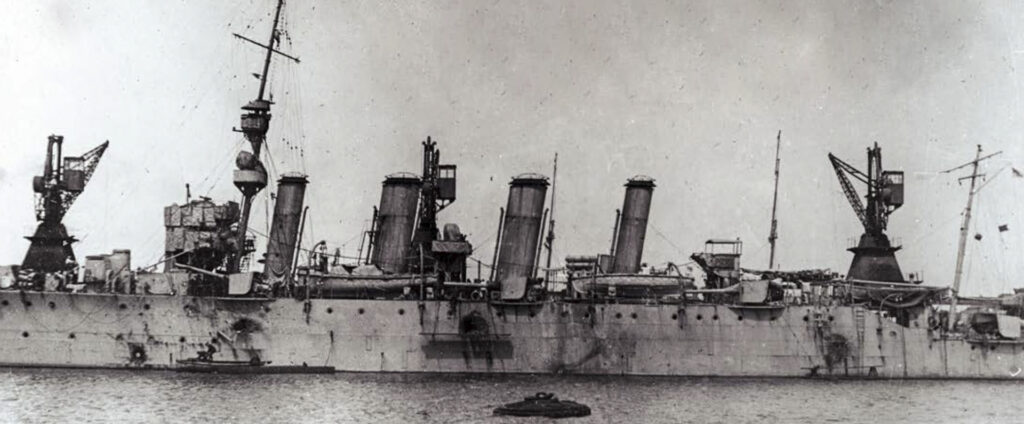

Jack Cornwell initially served as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class and his entire naval career would last only ten months. After receiving additional training as a gunner, he was promoted to Boy Seaman 1st Class in January 1916. On Easter Monday 1916, Cornwell left for Rosyth, Scotland, and he was soon assigned to HMS Chester, part of Grand Fleet’s 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron.

It was in the late spring of 1916 that the Grand Fleet came up against the German High Seas Fleet near Jutland. Chester was scouting ahead of the 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron, under Rear-Admiral Sir Horace Hood, on May 31 when she turned to investigate distant gunfire. At 5.30pm, the ship came under intense fire from no less than four enemy cruisers and 78 men, a fifth of Chester’s complement, soon became casualties.

The shielded 5.5-inch gun mounting where Cornwell was serving as a sight-setter was hit at least four times. All the gun’s crew were killed or fatally injured except Cornwell, who, although seriously wounded, managed to remain at his post for more than 15 minutes, until Chester retired from the action with only one main gun still working. The ship had received a total of 17 hits and the situation on deck was dire. Many of the gun crews had lost lower limbs and they died from a loss of blood and shock.

Medics arrived on deck to find Cornwell the sole survivor from his crew, standing at his gun, shards of steel penetrating his chest and awaiting further orders. Chester limped back to port at Immingham, Lincolnshire, from where Cornwell was taken to Grimsby General Hospital for treatment. However, he died there shortly before 8am on June 2 1916. By the time his mother, Lily, reached the hospital, her son was already dead.

Initially, at the request of Cornwell’s mother, his body was returned to London and interred at Manor Park Cemetery in a common, or “pauper’s” grave. However, when news of his bravery spread, the public demanded a more fitting send-off. Newspapers, notably the Daily Sketch, also latched on to the story and criticised the Admiralty for failing to give the “boy hero” a fitting funeral. Indeed the Daily Sketch promised to ensure that “his memory and his family are not forgotten”. Questions were even raised in the House of Lords and pressure grew for the award of a posthumous VC and a new burial.

Jack’s mother learned of her son’s bravery in a letter from the Chester’s commanding officer, Captain Robert Lawson. He wrote “I know you would wish to hear of the splendid fortitude and courage shown by your son during the action of 31 May. His devotion to duty was an example for us all. The wounds which resulted in his death within a short time were received in the first few minutes of the action. He remained steadily at his most exposed post at the gun, waiting for orders. His gun would not bear on the enemy; all but two of the ten crew were killed or wounded, and he was the only one who was in such an exposed position. But he felt he might be needed, and, indeed, he might have been; so he stayed there, standing and waiting, under heavy fire, with just his own brave heart and God’s help to support him. I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was, and what he did, and what an example he gave. I hope to place in the boys’ mess a plate with his name on and the date and the words: ‘Faithful unto Death’. I hope some day you may be able to come and see it there. I have not failed to bring his name prominently before my Admiral.”

Captain Lawson, forced on to the defensive by the Press, also issued a public statement explaining that, but for Cornwell’s mother having his body removed from the hospital to her house, the young hero would have had a funeral with “full naval honours”.

Eventually, a second, far more lavish funeral was held on July 29. A huge crowd lined the route as Cornwell’s coffin, draped in a Union flag and resting on a gun carriage, was for a second time taken to the cemetery. Shops were closed and many local dignitaries, including politicians, attended the event. In a moving eulogy, Dr F.J. Macnamara, Financial Secretary to the Admiralty, said: “Boy Cornwell will be enshrined in British hearts as long as faithful, unflinching devotion to duty shall be esteemed a virtue amongst us.”

Moreover, a posthumous VC for Cornwell was announced in The London Gazette on September 15 1916 when his citation stated: “The King has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of the Victoria Cross to Boy, First Class, John Travers Cornwell, O.N.J.42563 (died 2 June 1916), for the conspicuous act of bravery specified below. Mortally wounded early in the action, Boy, First Class, Jack Travers Cornwell remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders, until the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded all round him. His age was under sixteen and a half years.”

A new wave of emotion swept the country and there were several memorials to Cornwell’s courage. His face appeared in new portraits, on stained glass windows and on stamps. John Winton, the historian, later described the events as “a convulsive spasm of collective commemoration”. Cornwell’s mother received his posthumous VC from King George V in an investiture at Buckingham Palace on November 16 1916.

Sadly, by then the family had suffered a further tragedy. Eli Cornwell, Jack’s father, died from bronchitis on October 26 1916, while on active service with the Royal Defence Corps and his body was placed in the same grave as his son. Two years later, Arthur Cornwell, Jack’s elder half-brother, was killed in action while serving in France. Lily Cornwell, Jack’s mother and Eli’s widow, fared little better after all her losses: she died in her bed on October 31 1919, aged only 48.

Her last years had been spent impoverished after she was forced to move from the family home into some modest rooms in Stepney. However, after her death, the Navy League provided a grant of some £60 a year to assist in the care of her two youngest children.

More than a year after the war ended, The Daily Telegraph of November 26 1919 said of Jack Cornwell: “The story was in the minds of the whole Empire how a boy showed what a boy could do in the way of making history, and giving an example of how English boys should live and how English boys should die.”

Today Jack Cornwell has an impressive gravestone at Manor Park Cemetery in what is now called “Cornwell Crescent”. The inscription on it reads, “It is not wealth and ancestry but honourable conduct and a noble disposition that makes men great.” There are many memorials to him close to his family home including “Jack Cornwell Street”, a block of council flats called “John Cornwell VC House” and a public house called “The Victoria Cross”. As far away as the Canadian Rockies, a peak in High Rock Range, British Columbia, is called “Mount Cornwell”. In 1929, Walton Road School, where Jack had been educated up to the age of 14, took his name in its title.

I do not own the Cornwell VC even though it is on display at the gallery bearing my name at the Imperial War Museum, London. Jack Cornwell’s elder half-sister, Alice, gave Jack’s VC to the IWM on a “long loan” on November 27 1968 and the medal has remained there ever since. Jack Cornwell is the third youngest recipient of the VC in the decoration’s 166-year-history, with two 15-year-olds, Andrew Fitzgibbon and Thomas Flynn, both receiving their awards during the 19th century.

As Stephen Snelling wrote in his book VCs of the First World War: The Naval VCs, “In death Jack Cornwell achieved a kind of fame that he could not have dreamt of during his short life. His action, coupled with his extreme youth, touched off a wave of popular sentiment and public mourning that was unparalleled during more than four years of war. Myth and reality became so intertwined as to be almost inseparable and the ‘boy hero of Jutland’ came to stand as a symbol for a generation of doomed youth.”

Download a PDF of the original Britain At War article.

For more information, visit:

LordAshcroftOnBravery.com