Published in Britain at War in September 2021.

Captain Richard Phillip Carr MBE, MC

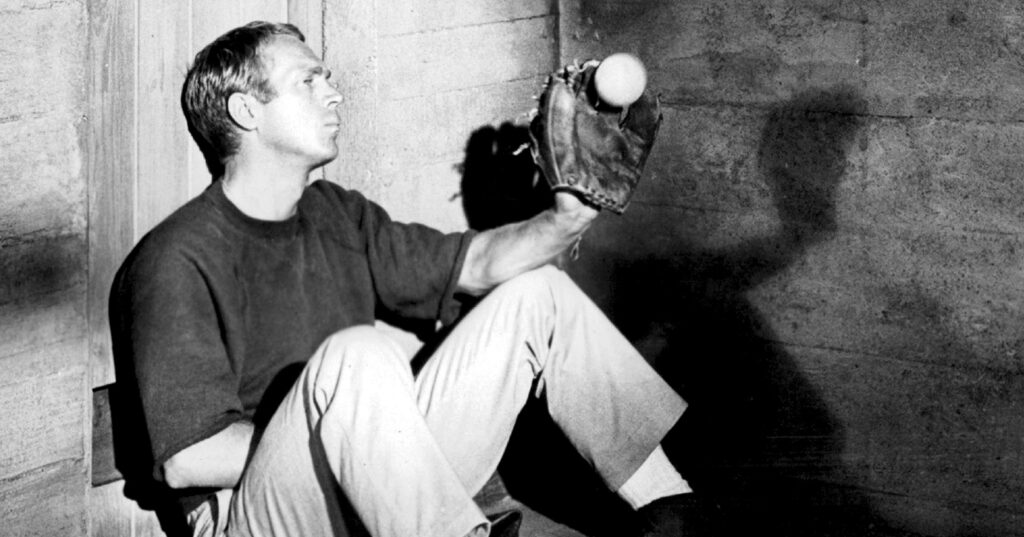

Richard Carr has been likened to “the Cooler King”, the charismatic character played by Steve McQueen in The Great Escape. In the 1963 American film set in 1944, McQueen plays Captain Virgil Hilts, who kept being returned to solitary confinement after repeated attempted break-outs as a prisoner of war. In real life, Captain Carr was equally vigorous in his escape bids, making no less than four determined attempts to gain his freedom and rejoin the war effort. Carr himself was modest about his escape attempts, describing them as “four real breaks and a few minor ones”.

Richard Phillip Carr was born in 1920, the son of a businessman who ran a large biscuit-making company. Little is known about his younger years but, by early in the Second World War, he was serving with the Royal Artillery in France, where he proved to be a regular and quite splendid letter-writer. If ever there was a man relatively unfazed by the horrors of war it was the cool, calm and collected Carr, as his informative letter to his father, dated May 22 1940, testifies: “ I am dreadfully sorry that I have not written before, but we have been terrifically busy. It’s extraordinary how used you become to being shot at, bombed by, machine gunned and shelled at by those bloody Germans, but the more they do it the less it worries. I can’t describe the things I’ve seen because it’s all so absolutely amazing, but I am well and feeling in cracking form and I must say we laugh a lot.

“For instance, the other day 42 German aircraft attacked the building I was in, making the most frightful din but not hurting anyone! Where I am now is like a city of the dead, not a soul about; you just go into any house you want to and take what you want; stray dogs are wandering about; everything half in ruins; it’s all so grotesque. But it’s such a rest from the last few days that it feels marvellous.

A Spitfire is at this moment in the process of bringing down one of those bloody Germans. Ah yes! I can see the smoke going up where he crashed – just one more out of his many hundreds. Don’t worry about this War since I am sure that at the moment it’s not as bad as that of 1914. I felt sorry for the German Tanks that come under my gunfire since it will put them straight out! The weather is superb and I am sitting out in the open at 4 a.m. writing this. The War has certainly made me see the dawn!

“It would be terrific if you could send me some Bourbon and Chocolate Biscuits as soon as possible since one never seems to have enough food on these occasions. I simply must stop now since I must go on my rounds and see what’s going on this morning.”

Incredibly, just six days after writing this boyish and enthusiastic letter, Carr, still only 20 years old and a 2nd lieutenant, was involved in the action for which he would later receive the Military Cross (MC). It was for his outstanding bravery during the retreat to Dunkirk that he was awarded his decoration, which was announced on August 27 1940, when the recommendation stated: “2nd Lieutenant Carr was left in command of his Battery on the 28th May 1940, when his Battery Commander and Battery Captain became casualties, and he showed great qualities of leadership and initiative during that day and during the subsequent withdrawal from Ypres Comines Canal. 2nd Lieutenant Carr has throughout displayed great powers of leadership and by his coolness under fire and contempt of danger has set a high example to all ranks.”

Following a period at the 42nd General Hospital as the result of an apparent small wound or illness, Carr volunteered for service with the Commandos. He joined 11 Commando on August 28 1940, serving with No. 1 Troop. After Carr was sent to the Middle East, it is believed he took part in the famous Litani River Raid of 9/10 June 1941. It was during this raid that his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Pedder, was killed. In a letter to a friend – dated 3 July 1941 and giving his address as ‘C’ Battalion, Layforce, Middle East Forces – Carr says Pedder is “a great loss to us, life is very different without him.’ Carr added: ‘I have travelled thousands of miles by air, sea, land,” but added “I am beginning to dislike the Middle East intensely.”

Carr appears to have served in Layforce, the British Commando unit commanded by Colonel (later Major-General) Robert Laycock, during September 1941 and then transferred to the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), where he was appointed as adjutant. In January 1942, Rommel’s Afrika Korps made a surprise attack, gaining ground quickly, resulting in a rapid withdrawal of the British forces. Carr was given command of a seven-vehicle patrol ordered to Msus, Libya, to collect valuable stores and to carry out a reconnaissance of the area. However, the German advance was so swift that it had captured Msus and Carr’s patrol drove straight into them. Carr was taken as a PoW to Italy: it was here that he wasted no time in trying to escape, making his four determined, but eventually unsuccessful, break-outs in just over two years. A letter home, dated January 17 1944, while he was still a PoW, indicated how hard It was for him as he tried to keep up his spirits: “I must say that letters from me have, after two years, become rather pointless, except to tell you that I am safe and well. After a few days in hospital with a touch of ’flu, I am both ‘Safe and Well’!

. . . There are a few lines left and I find it very hard to know what to say. My experiences would fill a book, so many worlds have crashed about my head during the last six months that sometimes I lose faith and hope in everything; but of course that is ridiculous.”

Even as a PoW, he was a regular letter-writer and a considerate son. On November 1 1944, he wrote to his father: “Many congratulations on completing 40 years in the business. How I wish I had lunched with you on that day. We’ll have just as good a celebration on my return won’t we?” In the same letter, Carr tried to be optimistic about his life after the war ends: “But here’s to the future; the past is dead. I’ve all my life ahead. A wonderful job, independence, security; surely with those ingredients I can make happiness? It is that thought which makes the next few days, weeks, months, whichever it may be, bearable, because viewed dispassionately what are a few weeks out of a lifetime?”

Carr was eventually freed as the Germans retreated in the face of the Allied onslaught in April 1945.

His MBE (Military Division) was announced on January 1 1946, when his citation stated: “Captain Carr was captured at Msus on the 26th January 1942. At Camp 35 Padula on 13th September 1942 he and thirteen others escaped through a tunnel which had taken them 1½ months to construct. Outside the camp the party split up and Captain Carr with one other started out in the direction of Switzerland. They were recaptured by Carabinieri 7 days later when forced to seek shelter at a farmhouse in the hills near Titopotenza. As a result of his escape Capt Carr was sent to Camp 5 Gavi and did one month’s cells as punishment. His second attempt was made after the Germans took over camp 5. In September 1943 he and another Officer had prepared a small hideout beneath the stairs and were sealed in an hour before the camp was due to move. About 58 others had also hidden themselves and at the last moment their absence was noticed. After a hunt lasting all day and most of the night, during which the German guards threw hand grenades indiscriminately, Captain Carr and his companion were dragged out of their cramped and airless quarters at 3 am and beaten up before being taken to Mantua and thence with others by train to Stalag VII A Moosburg. On the 5th October 1943 Captain Carr and an American Officer walked out of this camp dressed as French workers and walked to Munich, where they parted and Captain Carr with the assistance of French workers, boarded a goods train bound for Strasbourg. He had been given the address of a helper at Vendhelm but was unable to get in touch with him and while trying to find him in one of the barges on the cannel [canal] at Detweilie, was arrested by a German Policeman. Taken to Oflag VA Captain Carr took part in digging a tunnel, but before they could use it 120 Officers including Capt Carr were moved by train to Stalag VIIIF. On the second day of the journey (6th January 1944) while the train was going fairly fast Captain Carr and another Officer escaped through the netted window of their truck and jumped from the train. Captain Carr broke a finger and was completely winded but his companion’s face was so badly cut that he had to give himself up at Neurode next day. Captain Carr who was wearing his battledress was arrested at Oppeln and after an unpleasant interview with a Gestapo agent in Neurode and time in the cells at Gorlitz, he was returned to Stalag VIIIF, given five days hospital treatment and a week in the cells. In May 1944 all the prisoners were loaded onto trucks, handcuffed together and taken to Stalag 79 at Brunswick. Almost immediately Captain Carr walked out of the camp through a partially finished sewer but was caught when he returned to fetch his kit. He remained in this camp until his final liberation in April 1945.”

Carr left the Army at the end of the war and joined his family business, Carr’s Biscuits. He also became a keen sailor and a member of the Royal Yacht Club. He died, aged 58, on December 24 1977 after a brief illness. An unidentified friend wrote a short obituary that was published in at least one national newspaper early in 1978: It began: “The death of Mr Richard Carr, MBE, MC, on Christmas Eve at the age of 58 came as a great shock to his friends. He faced his short illness with the same courage that he faced life, and those who took part with him in his many escapes as a prisoner of war marvelled at his physical courage in the face of danger.”

I feel hugely privileged to be the custodian of this wonderful man’s medals, letters and other memorabilia. For Carr was a soldier who displayed “cold”, or premeditated, courage time and time again.

Download a PDF of the original Britain at War article

For more information, visit:

LordAshcroftOnBravery.com