Published in Britain at War in November 2020.

Petty Officer George McKenzie Samson VC

Petty Officer George Samson was the recipient of a superb Gallipoli campaign VC. It was the first such medal to a rating of the Royal Naval Reserve and gained during the landing at V Beach, Cape Helles.

George McKenzie Samson was born in Carnoustie, Forfarshire (now Fife), Scotland, on 7 January 1889. He was the second son – and one of nine children – of David Samson, a shoemaker, and his wife Helen (née Lawson). A restless soul, he was educated at Carnoustie School, where he often played truant.

After leaving school, he went to work on his uncle’s farm in Arbroath but he ran away determined to embark on a life at sea, although he was initially rejected on the grounds of his young age. Aged seventeen, he was employed by a Forfarshire cattle dealer to take thirty prize bulls to Argentina.

Once that task was completed, Samson travelled inland and found work as a cowboy on a cattle ranch. A year later, he returned home and enlisted in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, but bought himself out after basic training in favour of returning to sea, this time on a whaling trip to Greenland.

As a merchant seaman, he embarked on many adventures, including a voyage from Leith to Smyrna, Turkey, where, in 1912 and then aged twenty-three, he worked at the gas works prior to becoming a fireman on the railway line between Smyrna and Adana.

Like many merchant seaman at the time, Samson enrolled into the Royal Naval Reserve and, after the Great War broke out in August 1914, he headed for Port Said, Egypt, and then for Malta, where he joined HMS Hussar.

It was on this ship that he found his way to the Dardanelles in 1915. In a letter home written in early 1915 Samson said: “We are having awful weather here, and the ship has been trying to stand on her head for the last fortnight, but not managed it yet. The cold is much worse than the Germans, the only difference being that you can feel the cold but not see it, and see the Germans not feel them. We are all very anxious to have another go at them and get it finished.”

As a result of his travels, Samson could speak both Greek and Turkish, and he was regularly called upon to act as an interpreter for Rear-Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss. His linguistic talents also enabled him to join Commander Edward Unwin’s flat-bottomed steam hopper, the Argyll, for the forthcoming landings at V Beach.

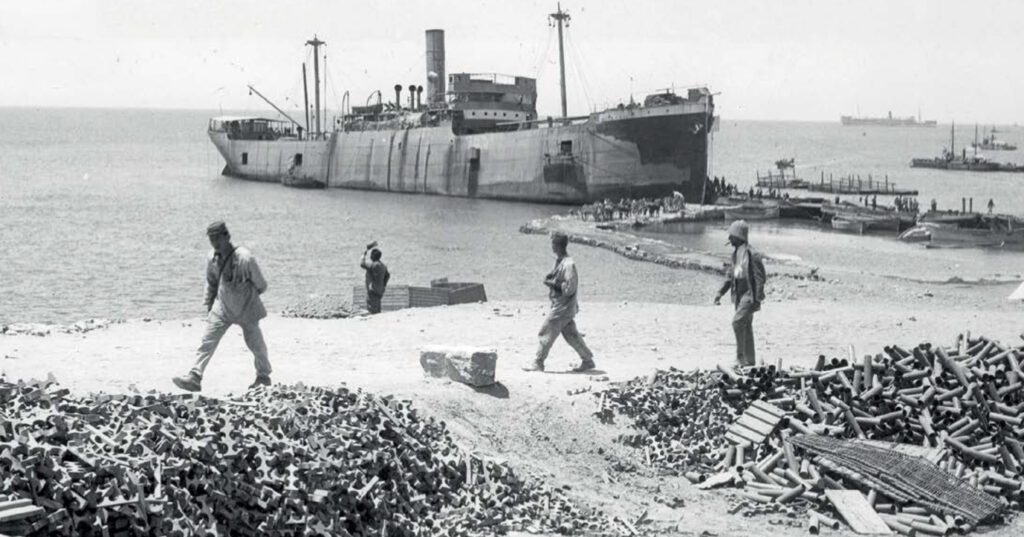

V Beach was some 300 yards long and was dominated by Sedd-el-Bahr, an old fort at its eastern end. On 2t5 April 1915, it was the landing place allotted to the Dublin Fusiliers and the Munster Fusiliers as part of the Gallipoli landings. The plan was that, after the initial landings, more troops would be brought in on SS River Clyde, a specially modified collier. The intention was to run her aground just offshore, with the gap between the River Clyde and the shore to be bridged by Argyll.

The attack was scheduled to take place at dawn: on board the steamship Unwin took Samson, Midshipman George Drewry and six Greek seamen, all clambering aboard at 5am. However, events did not go to plan after the incoming force at V Beach was met by a murderous enemy fire and Argyll was grounded too far from the River Clyde to be of immediate use.

Unwin himself leapt into the water and with Able Seaman William Williams, who had been aboard the River Clyde, dragged the lighters – large, flat-bottomed barges – forward to form a bridge to the shore via a shoal of rocks which jutted out into the sea from the fort. With nothing to attach the mooring ropes to, Unwin and Williams stood in the water holding the ropes to keep the two craft in place.

As the Munsters started to land, they faced a hail of bullets and many men fell, dead and wounded. When Williams was fatally wounded by a Turkish shell, the link to the shore was cut. It was at this point that Midshipmen Drewry and Wilfred St Aubyn Malleson, along with Samson, were able to form a bridge of lighters between the River Clyde and Argyll.

Drewry later provided a detailed account of the events that morning: “Shells began to fall round us thick but did not hit us. We were half a mile from the beach and we were told not yet, so we took a turn round two ships. At last, we had a signal at 6 am and in we dashed, Unwin on the bridge and I at the helm of the hopper … At 6.10 am the ship struck, very easily she brought up, and I shot ahead and grounded on her port bow. Then the fun began, picket boats towed lifeboats full of soldiers inshore and slipped them as the water shoaled and they rowed the rest of the way, the soldiers jumped out as the boats beached and they died, almost all of them wiped out with the boats’ crews …

“And it was under such desperate circumstances that Samson commenced his gallant work, bringing back wounded from the beach, and repairing the pontoon of boats and lighters started by Unwin and Leading Seaman Williams, the water now red with blood and whipped by devastating enemy fire – even so, he left the steam hopper on 30 occasions.”

Samson, himself, said: “The hail of bullets from the Turkish rifles was beginning to take its terrible toll, and I soon sound fresh duties to perform – that of carrying the wounded from the shore to the hopper, from which they were, as soon as it was possible, transferred to the River Clyde…I cannot say that I felt quite as cool as I may have looked. I am not a very excitable sort when there is serious trouble about. It takes a good deal to disturb me, but I can say without hesitation that this was the ‘goods’ for excitement.

“During these first hours…I had amazing narrow escapes just the same, of course, as my companions … Bullets were whizzing about our heads every few minutes, and we were soon aware of the fact that machine-guns were in operation … Men were falling down like ninepins quite near us, and perhaps it was only the thought that we must give them a helping hand that made us forget our own danger.”

Samson continued: “This time I began to think that any moment would be my last. Indeed, it became so hot that I finally decided to make a bold bid for safety. I began to roll over towards the side of the little vessel. There was no rail, and the fact was very much in my favour, for I was able to keep low down all the time. Bullets were flying all about the deck; once again I seemed to bear a charmed life … When I reached the side of the hopper I gave myself a big lurch, and fell into the sea. The sea was extremely choppy but … I was a good swimmer, and I did not find the slightest difficulty in getting back to the ship.”

At around 1.30 pm on the following day, with the beach-head more or less secure, Samson, already wounded and having been on the go without a break for some thirty hours, was hit by a burst of enemy machine-gun fire. He suffered multiple hits on his left side, but dragged himself back to his feet, only to be hit yet again.

By the time he had been brought before the River Clyde’s surgeon, Dr P. Burrowes Kelly, it was touch and go whether he would pull through, with nineteen separate wounds to his body. Later Burrowes Kelly said: “He was in great agony when I saw him and, whether he lived or died, I knew he had won the VC.”

On 16 August 1915, Unwin, Malleson, Williams, Drewry and Unwin were all awarded the VC for their bravery at V Beach. Samson’s brief citation simply read: “Worked on a lighter all day under fire, attending wounded and getting out lines; he was eventually dangerously wounded by maxim fire.” A sixth man, Sub-Lieutenant Arthur Tisdall, had his VC for the same action announced later, on 31 March 1916, for his gallantry in rescuing wounded soldiers from the shore in a small boat.

Samson’s wounds were initially treated at a hospital in Port Said but he was later transferred to the RN Hospital Haslar in Gosport, Hampshire. While he was back in Scotland recovering from his wounds, and staying at his father’s convalescent home in Aboyne, surgeons had only been able to extract four of the suspected nineteen bullets in his body. The following day, he returned in triumph to his hometown, Carnoustie, where he was the star guest at an impromptu reception, the crowds cheering him as he made his way through the streets.

It was a rather different reaction to the one given him by a clergyman who had shared the same railway compartment as Samson earlier that day. With Samson yet to receive his new uniform and in civilian clothes, the former clergyman announced in a loud voice, “Look at that fine-looking young fellow. He ought to be serving his country instead of being a slacker.”

Samson’s investiture took place at Buckingham Palace on 5 October 1915 when he received his VC from George V. Samson married Catherine Glass on 31 December 1915 at the Huntly Arms Hotel in Aboyne, near Aberdeen. The couple went on to have two sons and a daughter.

After being promoted to petty officer, Samson was granted one year’s sick leave in June 1916. Sadly, however, much of his time was passed in assorted hospitals and he was discharged from the Royal Naval Reserve in 1917.

Eventually Samson decided to revive his career in the Merchant Navy, sailing out of Dundee as quartermaster of the tanker Dosina in late 1922. However, he fell ill during her voyage to the Gulf of Mexico in early 1923. Transferred to the SS Strombus, bound for Bermuda, he died from double pneumonia on 23 February, aged 34, still carrying thirteen pieces of shrapnel from his war-time injuries.

Samson was buried with full honours in the military section St. George’s Methodist Cemetery. A road – “Samson Close” – is named after the VC recipient in Gosport, Hampshire. I purchased the Samson VC at a Dix Noonan Webb auction in 2007 and am proud to be the custodian of this courageous man’s gallantry and service medals.

Download a PDF of the original Britain at War article

For more information, visit:

LordAshcroftOnBravery.com