Published in Britain at War in October 2020.

Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey Saxton White VC

The VC awarded to Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey White was one of only five of to submariners during the Great War. Furthermore, it was also the first and only time that the VC has been awarded to two different captains of the same submarine.

Geoffrey Saxton White was born in Bromley, Kent, on 2 July 1886. He was the son of William White, a Justice of the Peace, and his wife Alice (née Saxton). After his birth, his parents gave him his mother’s maiden name as an unusual second Christian name. White was educated at Parkfield School in Haywards Heath, Sussex, and Bradfield College, Berkshire.

He joined HMS Britannia in May 1901, when still only fourteen, passing out later that year. In 1902, he served in HMS Aboukir and in November of that year he was made a midshipman. Over the next seven years, he had a variety of postings, travelling all over the world and, after the second of two promotions, he obtained the rank of lieutenant in October 1908. In January 1909, he joined HMS Mercury, a Portsmouth-based depot ship for submarine training.

Submarines, defined as watercraft capable of independent operation under water, had seen some experimental prototypes before the 19th century. However, proper submarine design only took off during the 19th century, and they were soon adopted by several navies. Submarines for military purposes were first used widely during the Great War.

Within two years of his training, White was given his first submarine command – HM Submarine A11 in July 1911. This initial appointment – which was followed by a series of further submarine commands – came just a month after his wedding, when he married Sybil Thomas in Plymouth, Devon (the couple went on to have two sons and a daughter).

In April 1914, just four months before the start of the Great War, White’s first spell in submarines ended when he was appointed to the battleship HMS Monarch. This occupied his time for the early part of the war but in 1915 he returned to submarines when he was given the command of HM Submarine D6 in May of that year.

In August 1916, he was given the command of HM Submarine E14, and in October that year he was promoted to lieutenant commander. In December 1916, E14 carried out patrols in the Mediterranean and the following year it was one of four submarines sent to Corfu to strengthen the so-called Otranto Barrage.

The Otranto Barrage was an Allied naval blockade of the Otranto Straits between Brindisi, Italy, and Corfu, Greece. The blockade was intended to prevent the Austro-Hungarian Navy from escaping into the Mediterranean and threatening Allied operations there.

As the war broke out in August 1914, two German ships, Goeben and Breslau, succeeded in escaping from the Mediterranean through the Dardanelles. They based themselves in Constantinople from where they made occasional forays into the Black Sea. There was huge concern in the Admiralty that Goeben, in particular, a massive modern battlecruiser, would slip out of Constantinople and be able to wreak havoc in the Mediterranean and, possibly, beyond. Indeed these fears were a forerunner to those experienced by the Royal Navy in the Second World War when it was desperately anxious that the Bismarck, the formidable enemy battleship, would slip out of northern German and cause mayhem among the North Atlantic convoys.

In November 1917, following the Bolshevik revolution, Russia withdrew from the war. On 20 January 1918, Goeben and Breslau, now flying the Ottoman flag, sailed through the Dardanelles with the intention of attacking the British naval base of Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos.

However, after successful attacks on two British ships, both ships struck mines and, while Breslau sank, Goeben limped back to the Dardanelles. Despite striking a second mine, Goeben would have made it to safety were it not for the miscalculation of her commander who, as the ship neared Nagara Point, mistook a buoy and ran her aground. This presented the British navy and the Royal Flying Corps with a heaven-sent opportunity to sink the German ship.

After air attacks failed and much careful planning, including air reconnaissance, White and his crew of E14 were tasked with finishing off Goeben and the submarine set sail from Mudros on 27 January on a dangerous journey through mined seas and enemy shore batteries.

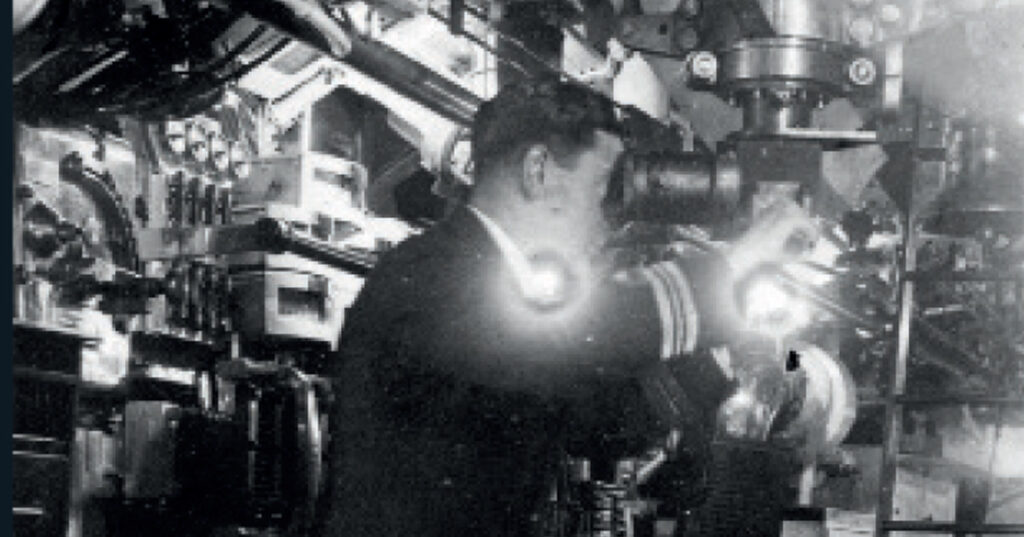

White and his men travelled by night to reach Nagara Point the next day. At 5.30am on 28 January, having negotiated the minefield safely, E14 advanced beneath the waves but soon it found her path obstructed by an unidentified object. White brought his submarine to the surface and climbed out to investigate, but only after giving strict instructions that the submarine must dive if attacked – leaving White himself to a certain death.

White guided the submarine clear of the mysterious obstruction and returned inside the submarine, confident he now had his bearings. It was light by 7am and White took a fix though his periscope. Nagara Point was clearly visible to him but there was no sign of Goeben: unbeknown to the British, the ship had been refloated some twenty-four hours before E14 embarked on its ill-fated mission. White took the submarine further up the Straits in the hope of spotting his target but, with no sign of Goeben, he faced the unappealing prospect of a dangerous return journey on depleted submarine batteries.

At 8.45am, White pushed up the periscope to take a fix and spotted a Turkish merchant ship within easy range. Perhaps to ease the disappointment of his failed mission, he decided to attack. However, just eleven seconds after the second torpedo left the submarine bow tube, E14 was rocked by a massive explosion. She was lifted up some fifteen feet and the conning tower rose out of the water. Furthermore, the forward torpedo hatch sprung open, enabling hundreds of gallons of sea water to enter. To this day it is not known what caused the blast but a torpedo may have struck a mine or exploded prematurely.

Immediately after the blast, the shore batteries opened up on the stricken submarine, which received several hits. Nevertheless, White gained control of E14 sufficiently well to submerge and assess the damage. For the next two hours, she limped along towards the open sea, with White hopeful that all was not lost.

However, a sudden surge of water then sent E14 plunging to 165 feet and, with virtually no control of the submarine, White was forced to bring her to the surface and run the inevitable gauntlet of guns from the shore. In a final attempt to guide his submarine and its crew, White climbed on to the casing soon after she reached the surface. With the conning tower flooded and its hatch jammed, he was forced to emerge from the fore-hatch.

By now the situation was hopeless as Petty Office Perkins, who survived the debacle, later detailed. He said: “The captain was the first one up on deck, and then the navigator [Lieutenant Drew of the Royal Naval Reserve]. I followed to connect up the upper steering gear. We found the spindle to be shot in half. Orders were given to steer from below. We ran the gauntlet for half an hour, only a few shots hitting us…The captain, seeing it was hopeless, ran towards the shore. His last words were, ‘We are in the hands of God’, and only a few seconds later I looked for him and saw his body, mangled by shellfire, roll into the water and go under. The last shell hit the starboard tank, killing all [in the area] I believe. By this time the submarine was close to the shore. Soon afterwards she sank…”

The shore fire had come from batteries on Cape Helles and Kum Kale. Perkins was convinced that Lieutenant Drew had been killed by the same shell that claimed White’s life. The Turks picked up only nine of E14’s 31-strong company, including Perkins and, after the war was over, they described the bravery of their commander and other men.

White’s VC was announced on 24 May 1919 when his citation ended: “Lieutenant-Commander White turned [his submarine] towards the shore in order to give the crew a chance of being saved. He remained on deck the whole time himself until he was killed by a shell.” Two survivors, Able Seaman Reuben Mitchell and Signaller Charles Timbrell were both awarded the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) for their bravery in keeping a badly-wounded comrade afloat until help arrived. Eight months later, on 22 January 1920, Petty Officer Perkins was also awarded the DSM, while Telegraphist William Prichard was awarded a Bar to his DSM. Two other crew were also awarded the DSM: Stoker 1st Class W.E. Reed and Engine Room Artificer R.W Milburn.

White’s VC meant that E14 became the only vessel in the Royal Navy’s history to have two of its commanders awarded Britain and the Commonwealth’s ultimate gallantry award. Lieutenant Commander Edward Boyle’s VC was awarded for his bravery in the Sea of Marmora, Turkey, when he avoided enemy patrols and mines in rough weather to launch a successful attack on enemy shipping.

Boyle’s award had been announced on 21 May 1915 when his citation read: “For most conspicuous bravery, in command of Submarine E.14, when he dived his vessel under the enemy’s minefields and entered the Sea of Marmora on the 27th April, 1915. In spite of great navigational difficulties from strong currents, of the continual neighbourhood of hostile patrols, and of the hourly danger of attack from the enemy, he continued to operate in the narrow waters of the Straits and succeeded in sinking two large Turkish gunboats and one large military transport [ship].” Unlike White, Boyle survived his VC action and the rest of the war. The two men had been friends through their Royal Navy service.

Quiet, modest, dedicated and much-loved by his crew, White was aged 31 when he died and his body was never recovered from the sea. His widow, Sybil, received his VC from George V in an investiture at Buckingham Palace on 12 June 1919. White’s name is remembered on both the Horley Memorial in Surrey and the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, Hampshire.

I purchased White’s medal group privately in 2016 and I feel immensely privileged to be the custodian of this brave man’s gallantry and service medals.

Download a PDF of the original Britain at War article

For more information, visit:

LordAshcroftOnBravery.com