Published in Britain at War in March 2013.

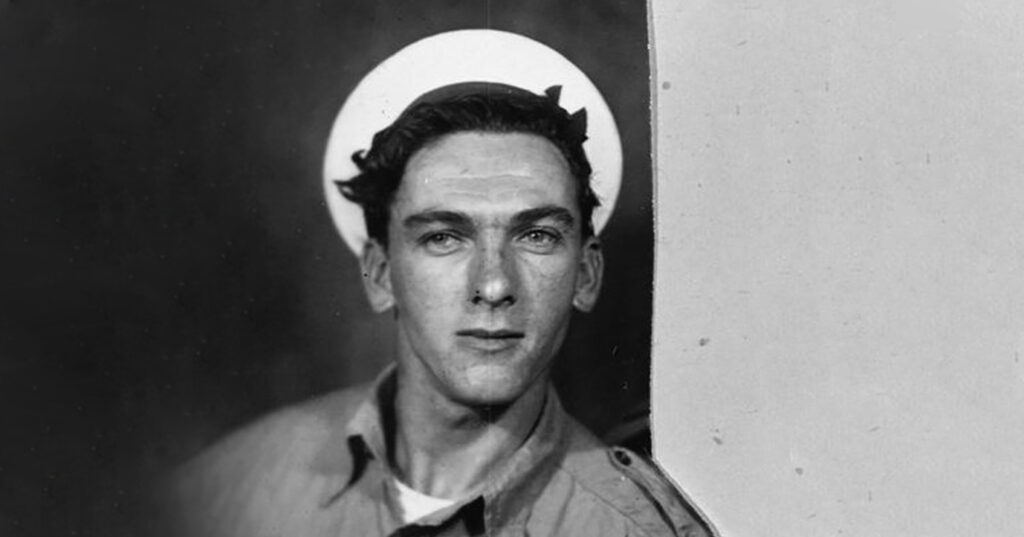

Acting Leading Seaman James Magennis VC

It was on July 30 1945, just a week before the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, that the four-man crew from the midget submarine were given their final orders.

Their task was to sink the Takao, a 10,000-ton Japanese cruiser that was moored in the Johore Straits, off Singapore. To get into position, however, they would have to negotiate treacherous seas – and then slip out again unnoticed before their explosives detonated.

The two key men in the midget submarine XE.3 were Lieutenant Ian “Tich” Fraser, who was in command of the mission, and Acting Leading Seaman James Magennis, the diver who would be tasked with attaching limpet mines to the hull of the enemy ship.

XE.3 was towed to the area by the conventional submarine, Stygian, before slipping its tow at 11pm on July 30. Ahead was a perilous 40-mile journey through wrecks, minefields, listening posts and surface patrols.

Conditions in the midget submarine were cramped, stuffy and uncomfortable although Fraser, at just five feet 4 inches tall (hence his nickname), could stand up inside without stooping.

For 13 and a half hours, their journey went without any hitches so that by 12.30pm on July 31 their target was in sight. At 1.52pm, Fraser began his approach and at 3.03pm – on his second attempt – he slid XE.3 under Takao. The enemy ship was anchored in shallow waters less than 100 yards from the Singapore side of the straits.

Magennis, 25, a Roman Catholic from a working class West Belfast family, had been a career sailor who had volunteered three years earlier for “special and hazardous duties”. Affectionately known as “Mick” to his comrades, he now faced the most daring operation of his career. Magennis slid out of the “wet and dry compartment” which could either be flooded or pumped to let a diver out or back into the midget submarine.

Soon he had begun his task of attaching limpet mines to the enemy ship. However, he had to chip away at barnacles in order to attach the magnetic explosives. Furthermore, the magnets were inexplicably weak so that, time and again, Magennis had to swim to retrieve them.

Eventually, despite a leak in his oxygen line, Magennis had attached six limpet mines to the hull before returning, exhausted, to the midget submarine. It was almost impossible for him to close the hatch because his hands had been shredded from tackling the barnacles.

Magennis later said of this part of the operation: “My first impression was how murky the water was. The bottom of the target resembled something like an underwater jungle and I had to clear a patch of undergrowth and barnacles off six places in order to make sure the magnetic limpets would stick on. Getting them on was quite like my old training days when I had stuck many dummies [dummy bombs] under our own ship. It took me about three quarters of an hour altogether before I got back to XE.3.”

Fraser now had to release two side charges from his craft, each containing two tons of Amatol, a high explosive. The port charge slipped away cleanly but the starboard one stuck to the midget submarine. Furthermore, on a falling tide XE.3 had become wedged beneath Takao and would not budge.

For more than an hour, Fraser struggled with XE.3 controls to break free but to no avail. It looked as if the midget submarine and her crew would be blown to pieces by her own explosives. There were only six hours before the charges went off.

Then, suddenly, the midget submarine shot backwards, out of control, surged towards the surface and caused a large splash just 50 yards from the cruiser. Fortunately, none of the Japanese crew saw what had happened and XE.3 dived back under the surface. Alarmingly, however, the starboard charge was still attached.

Knowing that Magennis was exhausted and injured, Fraser volunteered to dive to free it. Magennis, who had already displayed more than sufficient bravery to be awarded the VC, insisted that he was the more experienced diver and added: “I’ll be all right as soon as I’ve got my wind, sir.”

Soon Magennis slipped into the water again clutching a large spanner and, after struggling for seven minutes, eventually managed to release the charge. As soon as he was safely back in the midget submarine, XE.3 began her journey back at full speed, negotiating the same hazards that she had encountered on her approach.

Magnennis later said of this phase of the operation: ‘The water was muddy but when I looked closely I saw the lifting clips had not fallen away. I unclipped one, then the other. The midget submarine started to float away. I was still astride the side cargo. I had to swim for my life. Luck was with me. I made it. When I drained down in the wet and dry compartment and climbed back into the main section of the submarine, I was barely conscious. I remember Lt. Fraser saying, ‘You’re a gem, Mick’.”

Eventually, the crew made a successful rendezvous with Stygian and was towed to safety. The men had been 52 hours without sleep other than a short doze just before the attack.

Operation Struggle, as the mission was appropriately codenamed, was over and the charges that were laid blew a hole some 60 x 30 feet in Takao’s hull.

Fraser and Magennis were back on the base ship Bonaventure when information came through that they had been both awarded the VC. Even though it was 1am when the captain was told the news, he insisted on an immediate celebration. On a warm night off the coast of Australia, the crew partied until dawn.

Magennis’s VC was announced in the London Gazette on 13 November 1945 when his citation concluded: “Magennis displayed very great courage and devotion to duty and complete disregard for his own safety.”

He later recalled that he had been “proud but embarrassed” by the news of his decoration. Fraser’s VC was announced on the same day, while the other two crew, Sub Lieutenant William Smith and Third Class Seaman Charles Reed were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM) respectively.

The more that Fraser thought about Magennis’s role, the more admiration he had for his comrade. “Looking back on the limpet-placing part of the operation, I see how wonderfully well Magennis did his work,” Fraser wrote in his autobiography, Frogman V.C.

“He was the first frogman to work against an enemy from a midget submarine in the manner designed: he was the first and only frogman during the whole X-craft operations to leave a boat under an enemy ship and to attach limpet mines: in fact, he was the only frogman to operate from an X-craft in harbour against enemy shipping.”

On December 11 1945, Magennis and Fraser were presented with their VCs by George VI at Buckingham Palace. “Well done, my lad,” the King told Magennis. Fraser was also later made an officer of the US Legion of Merit for his bravery.

Both men late admitted that their VCs, although precious to them, also brought them unwanted pressures. The people of Wallasey – the town on the Wirral where Fraser had gone to school – raised more than £300 for him and also presented him with a sword of honour.

Fraser later said: “A man is trained for the task that might win him the VC. He is not trained to cope with what follows. He is not told how to avoid going under in a flood of public adulation. Three months after I received my VC I refused all invitation to functions in my honour. All this flattery had become dangerous.”

Although Fraser was wise enough to detect the danger signs, Magennis was not. As the only recent recipient of the VC to hail from Northern Ireland, he earned celebrity status in his home city.

The citizens of Belfast organised a “shilling fund” for their new hero that raised more than £3,000, a very considerable sum in those days. However, the money was quickly spent as Magennis succumbed to temptations and became too fond of yet another “celebration” drink.

His wife, Edna, later confessed that they had been ill-equipped to handle their stardom. “We are simple people. We were forced into the limelight,” she said. “We lived beyond our means because it seemed the only thing to do.” The couple, who married in 1946, had four sons but one, David, died young in a car accident.

Magennis, who left the Royal Navy in 1949, moved to Yorkshire in 1955, where he worked as an electrician, having long since squandered his riches. He died from lung cancer while living in Halifax, Yorkshire, on 12 February 1986, aged 66.

When his gallantry and service medals came up for sale later that year, I was able to fulfill a childhood ambition to purchase a VC, Britain and the Commonwealth’s premier medal for gallantry in the face of the enemy.

On a warm summer’s day – July 3 1986 – at Sotheby’s auction in London, I successfully, but anonymously, secured Magennis’s decorations for a hammer price of £29,000 (plus a buyer’s premium). Little did I know then that I would, over the next three decades, add another 178 VCs to that first purchase, thereby building the largest collection of such decorations in the world.

A memorial to Magennis was unveiled in Belfast in 1999 following a campaign led by George Fleming, the author of his biography, Magennis VC. Six years later, a mural commemorating Magennis on the 60th anniversary of VJ Day was also unveiled in the city.

In 1988 I took advantage of the opportunity of buying Fraser’s VC, thereby taking great pleasure in “reuniting” the two decorations for the first time since they were awarded in 1945.

Incidentally, Fraser, who after the war became a Justice of the Peace, remained in the Royal Naval Reserve until December 1965, when he retired as a lieutenant commander. He died in Wallasey on 1 September 2008, aged 87.

Download a PDF of the original Britain at War article

For more information, visit:

LordAshcroftOnBravery.com