In May 2006, the Information Commissioner, Richard Thomas, published “What price privacy? ”, a report into the unlawful trade in confidential personal information. In mid-December 2006, he followed-up his original report with a further interim document simply entitled “What price privacy now? ”. This provided additional illustrations of the extent of the trade, and reported upon the response of various national organisations to the earlier publication.

The first report had revealed that the Information Commissioner’s Office, otherwise known as the ICO, had long suspected the existence of an organised trade in confidential personal information; its suspicions being confirmed when, in November 2002, the ICO attended a search under warrant of the premises of John Boyall, a Surrey-based private detective, which was conducted by the Devon & Cornwall police.

Documents seized from the Boyall raid produced information which led detectives, on March 8th 2003, to mount a second raid, this time upon 3 Orchard Grove, New Milton, Hampshire, the address of Steve Whittamore, another private detective. 58year-old Whittamore and his wife, Georgina, had become the targets of an operation which by now had become code-named Operation Motorman. Bonnie & Clyde they may not have been, but deep in the heart of suburbia the Whittamores were discovered to be holding an Aladdin’s cave of information, most of it belonging to other people.

Trading as J J Information Limited, an apparently reputable business, this husband and-wife crime team, working with Boyall and with a number of others, offered a service to supposedly reputable organisations whereby they stole confidential information from, inter alia, telephone companies, the Driving & Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and even the Police National Computer. Helpfully, they had kept detailed accounting records for their enterprise in which they named their clients, the information requested, the information provided, and the price charged.

John Boyall, now of 3 Belvedere Road, Bromley, Kent, operated independently, trading as Liberty Resources & Intelligent Research Limited. Together, Whittamore and Boyall had a network of bent officials who would, for a price, supply ‘specialist information’. Central amongst them was Paul Marshall, a communications officer at Tooting police station, who retrieved information ranging from ex-directory telephone numbers and vehicle registration details to criminal records.

This information was then handed to Whittamore and Boyall via an intermediary, a retired policeman called Alan King. In February 2004, the CPS charged all four men – Whittamore, Boyall, King and Marshall – with conspiring to commit misconduct in public office. Each pleaded guilty yet, despite the extent and the frequency of their admitted criminality, each was conditionally discharged, raising important questions for public policy.

This was not just an isolated business operating occasionally outside the law, but one dedicated to its systematic and highly lucrative flouting. The Information Commissioner’s report “What price privacy? ” made clear, should there have been any doubt, that the customers of these villains could not escape censure for their actions. Only the deranged would imagine, for instance, that access to the Police National Computer could be obtained by lawful means. Nevertheless, customers came from a raft of organisations which one might have a reasonable expectation of being reputable. Media, especially newspapers, insurance companies and local authorities chasing council tax arrears all appear in the sales ledger of the dodgy agency.

Media represented the lion’s share. Operation Motorman seized files from Whittamore which named 305 journalists seeking information, and invoices and payment slips identified leading media groups. There was little attempt to disguise what was going on, the invoices referring openly to the supply of ‘confidential information’ and carrying VAT. (One is left with the disturbing thought as to whether criminal activity is indeed a ‘taxable supply’?)

The whole activity appeared in most respects to be a normal business, even to the extent of a published tariff of charges. Ex-directory telephone numbers cost the Hampshire detective £40, and he sold them on for £70. A vehicle check cost £70, and customers were charged £150. And so on.

The targets of the fraudulent enquiries included professional footballers, broadcasters and celebrities generally. They included a woman going through wellpublicised divorce proceedings and even a member of the Royal Household. Less obvious targets were the sister of the partner to a well-known local politician and the mother of a man once linked romantically to a Big Brother contestant. (Some people need to get out more.) Some targets, such as the self-employed painter and decorator who had parked his van outside a lottery winner’s house, seemed to be there completely by accident.

Little of this came as a surprise to me, for in 1999/2000 I had been the target of a dirty tricks campaign against me by Times Newspapers, the unpleasant details of which I recounted in my book ‘Dirty Politics, Dirty Times ’.

Various Times’ journalists, and even a Times Newspapers lawyer had employed third parties to gather information about me using illicit procedures of the kind detailed in ‘What price Privacy?’.

I was especially interested therefore in the contents of this report, and wrote about it in The Spectator (September 2nd 2006) . I also made a request to the Information Commissioner under the Freedom of Information Act asking for a breakdown of the numbers contained within his report. In relation to the media, his response was significant, showing a concentration of activity by a relatively small number of publications and by a limited number of very active journalists.

In revealing this information, I must make clear that the following figures are based only upon the raid on the Whittamores’ premises, and then only upon an analysis of data collected by the Information Commissioner covering the period from March 1st 2000 to March 8th 2003. (The first is the date on which the Data Protection Act 1998 came into force, and the second is that on which the Operation Motorman search warrants were executed and the ICO seized the revealing materials.) I should also emphasise that this is merely an analysis of one raid only upon just one private detective. I am told that Whittamore by no means had a monopoly during the period in question, but I do not know how many more private detectives were out there conducting similar ‘work’, nor do I know whether an analysis of Whittamore’s accounts represents in any way a representative cross-section of the activities of the media.

Moreover, I do not know whether the following pattern of behaviour by newspapers and magazines continues until the present day. Indeed, I have been told that certain publishers have called a halt to the practice, and that those decisions were taken even before Clive Goodman of the News of the World found himself in the dock at the Old Bailey!

Nevertheless, the ICO data released to me shows that the 305 journalists, the identities of whom have yet to be revealed, commissioned no fewer than 13,343 separate lines of enquiry from Whittamore. These transactions can be subdivided into three categories:-

- those which are positively known to have constituted Data Protection Act, of which there were 5,025.

- those in addition which were probably a breach of the a breach of the Data Protection Act, of which there were 6,330.

- those lines of enquiry which were questionable , but in relation to which there was insufficient information to form a definitive view, of which there were 1,988.

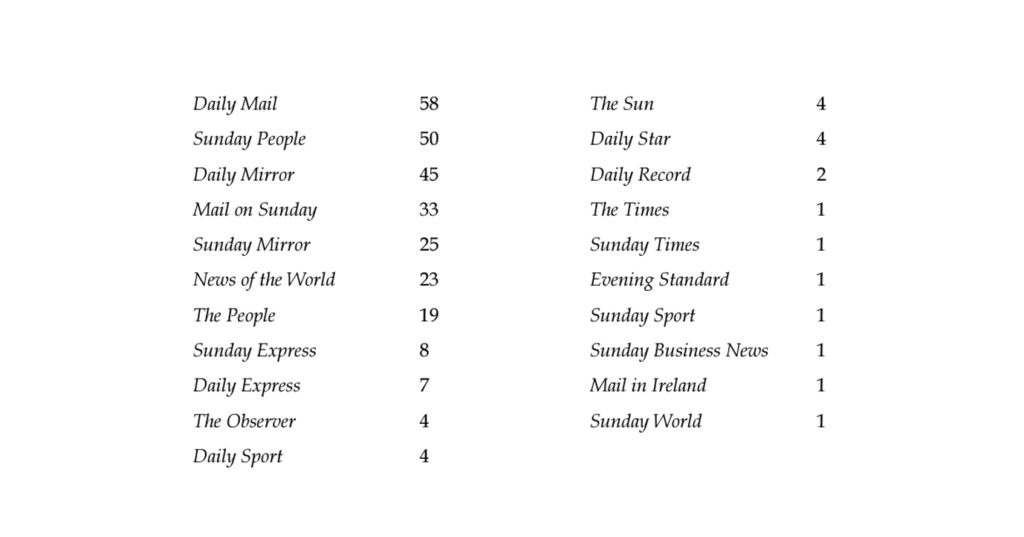

The 305 journalists worked for a total of 21 newspapers and 11 magazines, although some journalists worked for more than one publication. However, the concentration of activity was striking. One newspaper, for instance, employed no fewer than 58 journalists who commissioned illicit acts during the period. The numbers of individual journalists from each newspaper who commissioned information from Whittamore were:-

In total, 40 lines of enquiry were commissioned by journalists working for magazines, but half of these journalists worked for just one magazine – Best. No other magazine accounted for more than 5 journalists.

The identities of the newspapers and magazines is in fact now in public domain because they were also contained in the Information Commissioner’s second report, ‘What price privacy now?’. However, what was crucially absent from that report was the scale of separate lines of enquiry – 13,343! – and the frequency with which ‘orders’ were placed with Whittamore by each the 305 journalists. Just because orders in respect of a particular publication came from a multiplicity of journalists, it does not, for instance, mean that those journalists or, indeed, that publication, were also the most active. We do not yet know the identity of the publications to which the worst offending journalists were attached.

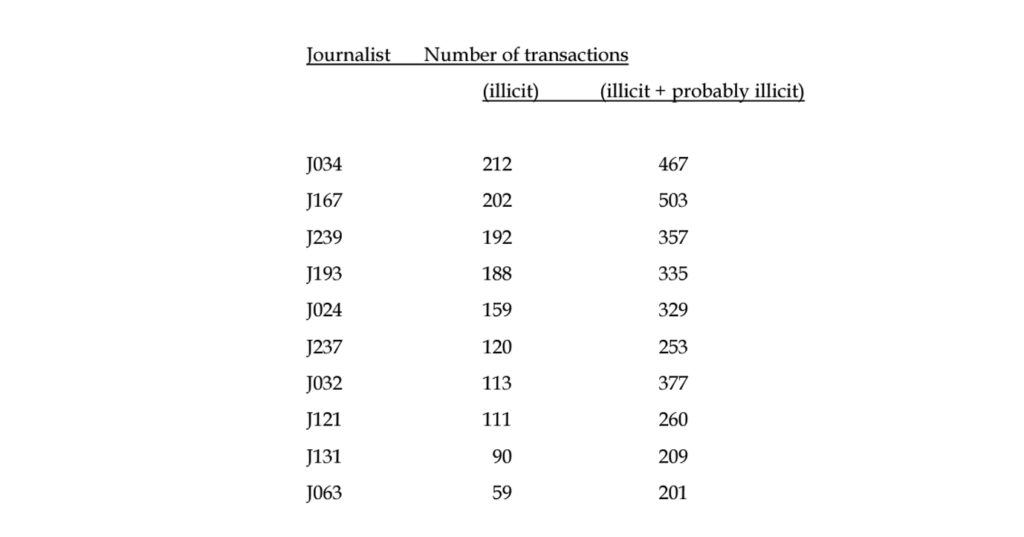

On average, the number of orders per journalist was 44. However, the ten most active journalists alone, out of a total of 305, were responsible for almost a third of all transactions.

Identified at this stage only by their ICO classification, the most active journalists were:-

In addition, journalist J239 spent the most of his employer’s money on this activity, commissioning transactions with an estimated cost of £26,000, although the ICO is silent as to whether VAT was on top of this figure!

My real sadness is that this both reports should have received such scant reporting from the press. It is understandable, perhaps, that few people would wish to stand up and be counted given what we all know goes on and to which so many blind eyes are turned. But ‘What price privacy?’ and ‘What price privacy now?’ should have featured large in the open debate as to what is truly acceptable in the pursuit of the public interest as opposed to what is acceptable in satisfying the prurient interest of the public.

I am led to believe that in the days of Fleet Street this sort of thing rarely occurred. Good journalists were nevertheless able to discover the information they needed, by largely legitimate means. I think it is right to have called time on a practice which does little to dignify the activities of a great profession.

It would though be wrong only to question the motives of the media. On November 14th 2006, for instance, another husband and wife team, Sharon and Stephen Anderson of St Ives, Cambridgeshire, were convicted at Huntingdon Magistrates Court of selling private financial information obtained by deception, on this occasion by the use of ‘blagging’ – making bogus phone calls to penetrate the details of people’s bank accounts and tax returns. Their clients were three private detective agencies working for international corporations and City firms, including leading solicitors. The Andersons allegedly refused to act for newspapers on what they said were “ethical” grounds.

Let me return though, if I may, to that unfortunate painter and decorator who parked his van in the wrong place. Representations have in the past been made to the Culture, Media & Sport Select Committee of the House of Commons to the effect that newspapers buy information only when it is in the public interest to do so. I am completely stumped, despite having a fertile and inventive mind, as to how acquiring the private information of an unconnected painter and decorator could possibly have been in the public interest?

Amongst the few reactions to the Information Commissioners have been a variety of preposterously cynical comments from a number of individuals within the media for whom, in most respects, I have the highest regard. I will not name them here but I would like to take issue with the sentiments which they have expressed collectively.

The common refuge that they have sought is the high-minded defence of free speech, arguing that there is nothing wrong in looking at the electoral register, or in searching the Land Registry, as though these were the very rights under attack. Both of these databases are of course available online, and there would be no need to go to the bother, or to the expense, of bribing a complex tier of public servants and dodgy intermediaries in order to gain access to such information. It is the very private nature of certain personal rather than public data which has stimulated the growth of an industry which relies upon deceit and illegality.

David Leigh, writing in the Guardian, had the honesty to admit that he had himself traded in such murky waters, but said, “I was not interested in witless tittle-tattle about the Royal Family. I was looking for evidence of bribery and corruption.” Perhaps he could do worse than looking at the activity of private detective agencies?

There has been no open debate within the pages of the very newspapers which have been at the heart of this trade. Instead, there has been a good deal of silence punctuated only by rather pompous pronouncements which it is claimed are in the furtherance of the public interest and free speech.

I would concede that there have been rare occasions when the goal might be seen to have justified the methods which were used to reach it. But the exceptions cannot be used to give justification willy-nilly to a raft of activity which has no such high ideals. And what happens if the perceived ‘bribery and corruption’ is proven by the facts (illegally discovered) to be merely illusory? Should those who breached the law en route to this discovery be instead sent to jail?

These are difficult and serious questions, in response to which no corresponding debate has yet taken place. If honesty were to replace the artifice, I wonder whether we might be able to reach a sensible conclusion?