Published in the Daily Mail on 19 August 2025.

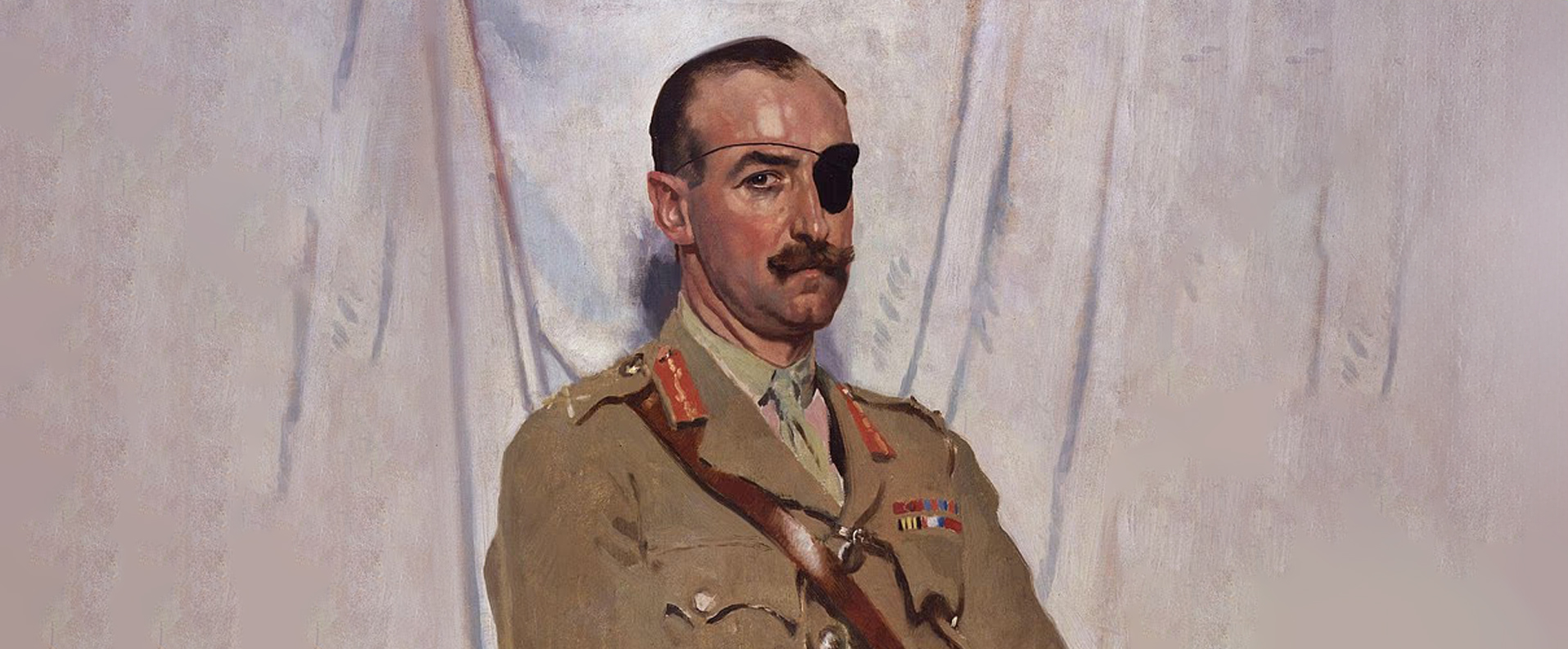

Now, the only surviving WWII VC holder has died at 105 – and the story of his courage holds as powerful a message today as ever.

For more than eight decades, his name was synonymous with duty, loyalty, sacrifice, humility and, above all else, courage.

Now Flight Lieutenant John Cruickshank, the last recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC) to fight in the Second World War, has died at the grand age of 105.

His passing, announced at the weekend, marks the end of an era. It seems appropriate that Flt Lt Cruickshank VC gave his final breath as the world was preparing to commemorate Victory over Japan (VJ) Day 2025 – marking the final conclusion of the 1939-45 war 80 years ago.

Cruickshank was – and is – significant in so many ways: the last surviving recipient of a VC for an action in the air and the last living Scottish recipient of a VC, the most prestigious gallantry award that Britain and the Commonwealth can offer.

In May 2020 he became the first VC recipient to reach the age of 100.

Yet the fact that this brave Scot lived beyond the age of 24 was in itself remarkable.

Cruickshank received no fewer than 72 separate injuries, including two wounds to his lungs and ten to his lower limbs. He almost bled to death.

For that’s how old Cruickshank was when, in July 1944, he carried out a quite remarkable act of bravery stretching over several hours above the freezing waters of the Arctic.

In attacking, and eventually destroying, a German U-boat from the air, Cruickshank received no fewer than 72 separate injuries, including two wounds to his lungs and ten to his lower limbs. He almost bled to death.

John Alexander Cruickshank was born in Aberdeen on May 20, 1920, the son of James Cruickshank, a civil engineer, and his wife Alice. He was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School, followed by the Royal High School and Daniel Stewart’s College in Edinburgh (today known as Stewart’s Melville College).

In 1938, Cruickshank was apprenticed into the Commercial Bank of Scotland. The following year, he joined the Territorial Army Gunners, joining the 129th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery at the outbreak of war.

In June 1941, Cruickshank transferred to the Royal Air Force and, after training in Canada and the United States of America, received his pilot’s ‘wings’.

Then, in March 1943 he joined No 210 Squadron of anti-submarine flying boats based on the Shetland Islands.

It was on July 17, 1944, that an RAF Catalina with a ten-man crew took off from RAF Sullom Voe. The pilot and captain was Flying Officer Cruickshank, by now, a veteran of 47 sorties.

Despite his serious injuries, Cruickshank pressed home the attack and released the depth charges himself, hitting the submarine directly

The task was to help provide anti-submarine cover for the British Home Fleet – the Royal Navy’s main European force – returning from Operation Mascot. This was an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the German battleship Tirpitz, then moored in Altafjord near Norway’s North Cape.

When a U-boat was sighted on the surface of the Norwegian Sea, F/O Cruickshank immediately turned to attack it. A German submarine was a great prize for any Allied air crew.

Despite anti-aircraft fire, he manoeuvred his aircraft to drop depth charges from a height of only 50ft above the water, but the charges failed to release.

Cruickshank knew he had lost the element of surprise and that the gunners aboard the submarine were now prepared.

Yet he resolved to approach the U-boat a once again. As F/O Cruickshank and his crew came in for a second time, they were hit by intense and accurate enemy fire.

The navigator/bomb aimer was killed. The second pilot and two other members of the crew were wounded, as was Cruickshank himself.

Despite his serious injuries, Cruickshank pressed home the attack and released the depth charges himself, hitting the submarine directly and causing her to sink.

Yet the Catalina was so badly damaged that it was filled with the fumes of exploding shells. And the surviving crew were more than five hours from their Shetland base, trapped in an aircraft that seemed unlikely to make it.

Cruickshank headed to the safety of a fog bank, where he calmly assessed the situation before turning back home.

The aircraft’s radar was out of commission. Fuel was leaking from damaged pipes. Shrapnel holes in the fuselage were stuffed with life jackets and canvas engine covers. Cruickshank’s wounds were so serious that he collapsed at the controls, leaving second pilot, Flight Sergeant Jack Garnett – whose injuries were less severe – to take over for a time.

Cruickshank’s wounds were so serious that he collapsed at the controls

Recovering his composure shortly afterwards, Cruickshank insisted on resuming command. He set a course for the base, sent out the necessary signals and only then, reluctantly, received medical aid for the worst of his 72 wounds.

Cruickshank refused a morphine painkiller, however, in case it prevented him from carrying out his duties.

Over the next five and a half hours, bleeding heavily, Cruickshank lapsed in and out of consciousness with Garnett taking the controls once again.

But with the aircraft only an hour or so from base, Cruickshank insisted on being carried forward and propped up in the second pilot’s seat. He knew that a hazardous landing in darkness was inevitable – and that Garnett lacked experience.

Despite struggling to breathe, Cruickshank gave instructions and encouragement on how best to land the Catalina, assessing both the light and the sea conditions before the flying boat came down in the water off the Shetland Islands.

Even at that point, Cruickshank insisted on giving instructions on how to taxi and beach the aircraft so that it could eventually be salvaged.

Cruickshank required a blood transfusion before he was removed from the aircraft and taken to hospital.

Throughout, he set an example of determination, fortitude and devotion to duty

The lengthy citation for his VC, announced in The London Gazette on September 1, 1944, concluded: ‘By pressing home the second attack in his gravely wounded condition and continuing his exertions on the return journey with his strength failing all the time, he seriously prejudiced his chance of survival even if the aircraft safely reached its base.

‘Throughout, he set an example of determination, fortitude and devotion to duty in keeping with the highest traditions of the Service.’ The second pilot, Flt Sgt Garnett, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM).

Cruickshank was discharged from Military Hospital, Lerwick, Shetland, later that same month.

He received his VC from King George VI in an investiture at the Palace of Holyrood, Edinburgh, on September 21.

After recovering from his wounds, Cruickshank served at Headquarters, Coastal Command, by this point holding the rank of flight lieutenant.

After the war, he resumed his banking career with postings to Asia and Africa. In May 1955, Cruickshank married a Canadian, Marian Beverley, in Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar). She died in 1985.

Flt Lt Cruickshank lived on his own for the next four decades.

You don’t get involved in that kind of thing – thinking of any decorations or any recognition. It was regarded as duty.

But each year, in a moving gesture that said so much about his character, he travelled to the Shetlands to lay a wreath on the grave of his navigator, Flying Officer John Dixon.

Bob Kemp, a fellow retired RAF officer and close friend said: ‘John was an amazing character, very quiet, but with a terrific sense of humour.

‘I flew with him in the Catalina when he was almost 90 and as soon as he got airborne his recall of the detail of the aircraft came alive.

‘He could point out every position of every crew member, where all the first-aid kits were stored, where all the machine guns were, the depth charge settings and the engine’s revolutions for take-off etc. His recall was magnificent.’

The death of Flt Lt Cruickshank was announced with no details about where he had died or the exact date of his passing. He was a private man and his funeral will be an occasion for close family and friends.

Cruickshank was one of 181 men to be awarded the VC during the Second World War, including a New Zealander who received it twice, a double award known as a VC and Bar.

Cruickshank’s death is, of course, a tragedy for his family and friends who loved him so dearly. But his place in history is secure – one of the finest examples of bravery it is possible to imagine from a generation of men and women to whom we owe so much.

He rarely talked about his war-time service and his VC, saying in 2008: ‘You don’t get involved in that kind of thing – thinking of any decorations or any recognition. It was regarded as duty.’

Like so many of the decorated war heroes that I have met over the years – as I built the world’s largest collection of VC medals – Cruickshank’s courage was matched by modesty and humility.

In 2013, and by that point in his early 90s, he said of that night’s bravery: ‘It was just normal. We were trained to do the job and that was it. I wouldn’t like to say I’m the only one who has an amazing story. There are plenty of other stories coming from that time.’

Today the world is once again a dangerous place, with wars and conflicts in eastern Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere.

It is all the more important, then, that we honour and cherish the valour of men like Flight Lieutenant John Cruickshank VC, who put his country, his monarch, his comrades and wider freedoms above his personal safety to make the world a better place.

Read this article on DailyMail.co.uk

DOWNLOAD PDF